Discovering Hemingway’s Havana

Share

Cojimar, Cuba. Cojimar, just a few minutes east of Havana is a picturesque fishing village where Hemingway docked his boat El Pilar. Not only did he use the town as a base for fishing, Cojimar was the background for one of his most famous works, The Old Man and the Sea. The Ôold manÕ in the title is reputedly his guide Gregorio Fuentes, a Cojimar local.

Inside one of Havana’s most famous bars, El Floridita, several dozen people are singing along to choruses led by a dynamic salsa singer. A circle of New York couples and an Argentine with two cigars stuffed in his shirt pocket all dance before the singer’s five-piece band. Most of the patrons have ordered icy daiquiris in thin-stemmed cocktail glasses, a famous drink from El Floridita, which turns 200 this year.

Seeming to watch all this is a bronze sculpture of Ernest Hemingway, the Nobel Prize–winning American author who lived in Havana from 1940 to 1960. Now he leans against the bar in the same spot where he was known to enjoy a dozen or so daiquiris a day.

After a half-century hiatus, Americans are returning to this island nation, just under 100 miles from Florida. I’m finding that Hemingway’s footsteps provide a timeless introduction, starting with his writings. To Have and Have Not begins in Plaza de San Francisco; parts of Islands in the Stream were influenced by his nights on the island; and his articles for Esquire talk about his offshore chase for marlin. He dedicated his 1954 Nobel Prize to the Cuban people.

Visitors can experience parts of Hemingway’s trail on bus tours, although I’m doing it on my own. The next morning I begin on Obispo Street, in the nearly 500-year-old Spanish colonial Habana Vieja, the city’s Old Town. The cobbled pedestrian street is packed with people browsing bookstores, musicians playing in doorways of cafes and bars, and coffee-sippers standing at popular cafes. Visitors queue up at an open-front pulled-pork sandwich shop with alluring aromas. I wander the book market that rims the plaza. Most vendors sell old paperback copies of Hemingway’s El Viejo y el Mar (The Old Man and the Sea). I buy a baseball poster of the Industriales, who could be considered Cuba’s New York Yankees.

At the nearby Hotel Ambos Mundos, I stop to ask about seeing Room 511. This is Hemingway’s old quarters, and the room is more or less as he left it. And for a small fee, visitors get a few minutes inside. I look at his typewriter, his fishing rods and the 1954 telegram letting him know he’s won the Nobel. Then I pause to take in the corner room’s view of hilltop forts, the harbor and colonial rooftops, essentially the same view Hemingway had when writing Green Hills of Africa here.

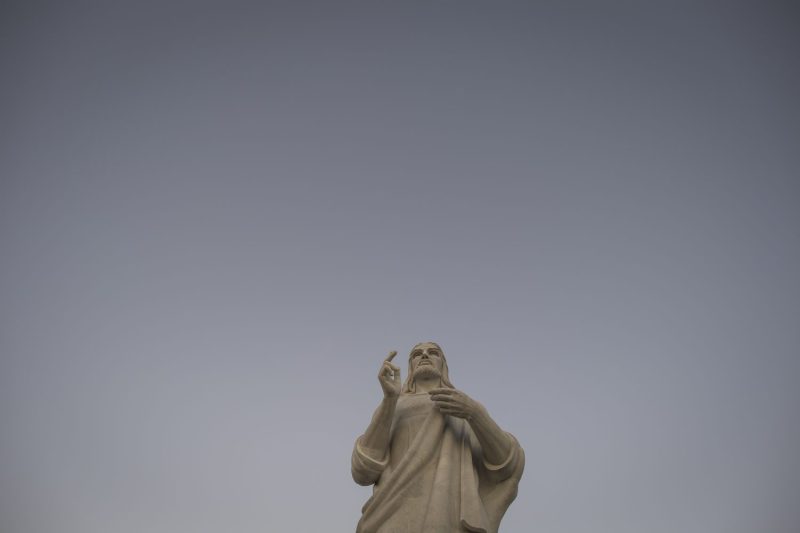

“See the Christ on the hill?” says a voice from behind me. I turn to see a Cuban guide pointing toward the Christ of Havana, a Carrara-marble statue of Jesus across the narrow harbor. “They put that up while Hemingway was here.”

Havana’s Old Town is best seen by foot. I love it at night, when narrow storefronts pour light onto couples chatting in shadowy narrow streets. The scent of cigar smoke wafts in the air. Beyond Old Town, getting around is even more fun. Havana’s colorful fleet of taxis spans the city’s last eclectic century. Modern Chinese and Korean imports join Soviet-era Lada and Moskvitch models, and American Chevys and Chryslers from the 1950s.

I hire one of the taxis to reach the next two big Hemingway spots, starting with Finca Vigía, about 10 miles southeast of Havana. This 19th century villa in San Francisco de Paula is the home where Hemingway lived longest in his 61 years.

Visitors can peek in from open doors and windows only, and can walk past the pool to a covered pavilion to see the writer’s beloved fishing boat, Pilar (subject of Paul Hendrickson’s excellent Hemingway’s Boat). Next to the house, a three-story tower commissioned by Hemingway offers panoramic views of Havana and the Gulf Stream beyond. “Looks like Africa,” I hear a French visitor say.

I make a quick pass around the house, pausing longest at Hemingway’s bathroom. On the wall, I notice his penciled scrawls that charted his (mostly rising) weight over the years. After gaining 10 pounds during a 1957 trip to New York, he noted: “17 days of diet—five drinking.” I see a biography of Houdini on a small shelf and a lizard in a jar. Curiosity piqued, I stop at the museum’s admin office to ask about the lizard.

“Hemingway’s old foreman once told me that one of his cats fought and killed that lizard,” says Ada Rosa Alfonso Rosales, the site’s director. “So Hemingway saved it, as a trophy for the cat.”

She volunteers to take me back to the house to show me her favorite item, a ceiba tree root. Facing the library, she points out the dried roots dangling over the doorway. “Hemingway was very superstitious,” she explains. “To cut a ceiba brings bad luck. So when this ceiba had to be removed, he hung the roots.”

Luck is an important theme in the Cuba-based story The Old Man and the Sea. Or rather the lack of luck. In the story, the old man fisher suffers from salao—“the worst form of unlucky”—then loses his monumental catch, after 84 days without one, to sharks.

The story is set in my next stop, a quiet seaside village about 7 miles east of Havana called Cojímar, where easygoing locals relax on benches and walk in the middle of the roads. I visit La Terraza, a restaurant where Hemingway enjoyed paella, and where visitors can now admire a decorated shrine to the writer. Down the waterfront malecón, a young Cuban couple in a long sun-soaked embrace sits before a Hemingway bust that faces El Torreón di Cojímar, a 17th century Spanish fort. I stand here a moment and listen to waves crash on nearby rocks. Ahead, seated on the pale blue wall along the waterfront, I spot a few hopeful teen anglers dangling a line into the water.

I move off the main streets to find the former home of the late Gregorio Fuentes, Hemingway’s former first mate who, some claim, is the inspiration for the story’s “old man,” Santiago. Fuentes passed away, at the age of 104, in 2002.

My driver tries to find the house, but the address I have (Calle 98, No. 209, at the corner of Calle 3D) is tough tracking. A few locals point in opposite directions, then finally a shirtless older man, looking at me through thickly lensed glasses, knows exactly where to go.

“Oh, he’s not alive! You know that?”

I tell him I do.

“Well, his little casita is that way,” he says, pointing the black machete he carries. “Two blocks.”

We find the simple white home with a small Hemingway sticker on the door. No one lives there. I snap a photo with my cellphone, satisfied with the quest.

I decide to make my way back to Habana Vieja by water, so I ask my driver to drop me off at the Casablanca port on the Havana harbor, where I join locals on the ferry. I stand between families in the open doorway and watch as we pass fort ramparts and see the sun shining over tiled rooftops. The short ride takes about five minutes to reach our destination.

After an afternoon of further exploring in Old Town, I stop in once more at El Floridita, this time finding a stool at the bar. The bartender, in a formal red-and-white uniform, mixes drinks and pours a line of fresh daiquiris. Though busy, he immediately stops to talk when I ask if he’s a Hemingway fan.

“Oh, yes,” he says in English. “The Old Man and the Sea is my favorite.”

The bartender, who tells me his name is Abel, has worked here for 24 years. He pours me a daiquiri while he gives me an impressive literary analysis of The Old Man and the Sea.

“I’m a fisherman. And I know what he was trying to say,” Abel says. “He knows us, the Cuban people. We always fight the big fish. It is the future. We just don’t know if we’ll get it or not.”

For the short term, Cuba can expect a new group of wide-eyed visitors, excited to appreciate the culture, food and history, and to better understand Hemingway’s passion for this country.

Robert Reid is a travel writer based in Portland, Oregon, whose writings have appeared in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He’s been the spokesperson for Lonely Planet, appearing on CNN, NBC’s Today Show and NPR to discuss travel trends. He’s currently the Digital Nomad for National Geographic Traveler. Photos by Ingrid Barrentine.